In Ben Affleck’s 2023 film Air, about Nike’s bid to make the young Michael Jordan’s shoe, there’s a blink-and-you-miss-it skateboarding scene. Affleck, as Nike founder Phil Knight, and Matt Damon’s Sonny Vaccaro are looking down from Knight’s office window into the parking lot below. Weaving and pulling out flips between the cars is Peter Moore, Nike’s forty year-old creative director.

SONNY: Is that Pete?

PHIL: What is Pete doing skateboarding in the parking lot?

SONNY: Maybe he’s having a mid-life crisis.

PHIL: I hope his mid-life crisis doesn’t scratch my Porsche.

The same year, another movie: Nyad tells the story of Diana Nyad’s bid, in her sixties, to make the hundred-mile swim from Cuba to Florida; a lifelong ambition which, after some aborted attempts, she finally realises. A refrain running through the film is the much-quoted final line from Mary Oliver’s poem ‘The Summer Day’, popping up Jiminy Cricket-like to nag Diana into action: ‘Tell me, what it is you plan to do / With your one wild and precious life’.

Nyad is about a seemingly impossible achievement, made seemingly more remarkable by the age of the person that does it. Diana is affectionately referred to by close friends as a bit bonkers, though not for her delusions, but for her ambition and drive. Diana herself knows how other’s might perceive her – ‘I don’t want to be the crazy old lady chasing an absurd dream’ – but no one tells her she is. In the film’s terms, she’s nothing short of heroic.

Back to Nike’s HQ, then, and Sonny finally gets to quiz Pete on his new hobby:

SONNY: Was that you in the parking lot, on a skateboard?

PETER: Yes.

SONNY: What’s that all about?

PETER: I’m having a mid-life crisis

End of discussion.

As you might guess, I find the differences between these two films interesting. I get that Pete’s role in Air is a bit of a sideshow to the main event, a passing gag intended to highlight the creative director’s eccentricity. But why make the balding shoe-designer’s efforts to skateboard the butt of the joke? (I’m tempted to flip it around, and ask the then-fortysomething Phil Knight why, of all the cars available, he’s gone and bought a Porsche).

No one suggests anything similar of Diana in Nyad, though, since it follows the logic of Oliver’s poem: later life and the remaining years, when literal and figurative retirement are bearing down, are exactly the time for doing crazy things and following absurd dreams. So where’s the difference between her and Pete? Where’s the fanfare he, too, deserves?

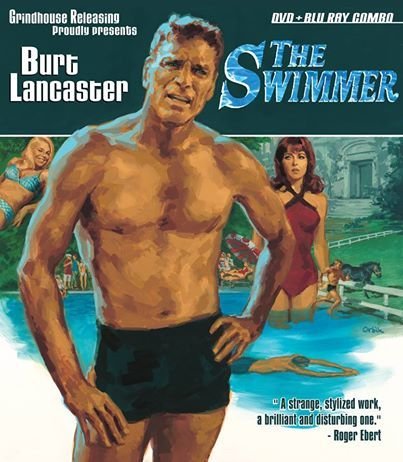

Calling someone out on their mid-life crisis, in many cases, is possibly justified; at least when it’s targeted at men of a certain age (and it usually is men) suddenly gravitating to younger, sexier models – of partner, of their own body image, and yes, of automobile – in some attempt to stave off their decrepitude and dwindling sperm count. And when seen as motivated by a similar urge (to get buff; to be more attractive; to look like a teenager again) the take-up of certain sports might carry the same connotations (including swimming: see the bizarre 1968 film The Swimmer as a case in point).

Maybe it’s because she was played by the sixty-four year-old Annette Bening, and not by the fifty-four year-old Burt Lancaster, as well as the lack of physical vanity about the whole project, that we’re less likely to talk of Nyad in the same terms. But the film suggests that we do recognise our mid- and later-life phases as ones in which major decisions and life choices both can and, maybe, need to be made. And rightly so, because it’s already a time of crisis.

Real life isn’t the movies. But the appeal of movies, and the way sports biopics like Nyad operate, is by drawing on parallels between the narrative of life and the essential structure of all stories, including Hollywood screenplays. Film plots typically have key ‘points’, usually where the protagonists confront change, setbacks or life-changing decisions. The most important of these comes about three quarters of the way through the film, before the final actions of the film are set in place: the moment, usually, of decisive action, of do-or-die. As it happens, some theorists call this moment, after the ‘disaster’, the crisis.

If we did want to plot our life like a screenplay, in chronological terms, this same life-point is one marked by a similar disaster, only one going on inside the skull. As the neuropsychologist André Aleman writes in Our Ageing Brain, fifty is on average the age at which major reductions in brain mass and volume start to occur. At the same age, deteriorations are also more likely to occur in the brain’s ‘white matter’. This is the part of the brain housing ‘axons’: the threads that carry signals between the brain’s neurons, which communicate so that we can remember things or work stuff out. Put simply, then, fifty plus is inevitably the age of significant cognitive decline.

After this, then, the crisis; or rather the choice. What does someone do when confronted by this disaster? Or put differently: what do you plan to do with what’s left of your wild and precious life?

As I’ve understood it, the broader view in neuropsychology these days is that, compared to the child’s more ‘plastic’ and growing brain, which makes new neural connections every time it discovers something new (which, basically, is all the time), older brains are more ‘set’. Neural pathways adults no longer need are in effect ‘pruned’ like the branches of a tree, leaving them only with the ones that are ‘essential’. This means adults are very competent at certain things, but it’s also the reason they find it harder to learn new skills, or – in fact – return to things they used to do but haven’t done for years. This might explain a lot of things, including the way many adults, confronted with the sheer undulating awesomeness of a skatepark, will more likely look at their phones, while their skateboarding kids literally inflate their minds.

The good news is that ‘neurogenesis’, or the growth of new neurons, even though it slows down, doesn’t stop completely after fifty. Later-life learners can learn new stuff, and create new memory- and skill pathways in the brain. As the psychologist Alison Gopnik writes, though, this is more likely to happen only ‘under pressure, and with effort and attention’. Or as Carl Honoré suggests in Bolder, one of numerous recent manifestos for the power of later-life adventure, the older brain can stay malleable by ‘adopting an experimental mindset, which means pushing yourself to seek out fresh challenges and try new things, especially those that hurt like burpees’.

Challenges, to take one example, like skateboarding.

Perhaps the real point in Air, which is set in the unenlightened 1980s, is that it’s everyone but Pete Moore who is living out a fantasy past. The designer’s embrace of skateboarding at the threshold of middle age (incorrectly, but intriguingly, the original script has his age down as 49, one year from disaster), is the sign that he’s the bright spark in the room, the one no longer, to paraphrase Honoré, ‘captive to the status quo.’ He did design the Air Jordan, after all. Not to mention the fact that, as a post on the site Skate and Annoy notes, he’s doing ollie kick-flips in 1984, before Rodney Mullen even made these widely popular. Genius!

The joke’s maybe on Affleck’s Phil Knight, who, when not driving his German sports car, is out on late-night runs. Anyone who’s actually tried an ollie kick flip, and then tried it again for the next hour, will know that, like jogging, skateboarding provides the aerobic boost seen as vital in keeping cognitive decline in bay. But – and again, if you’ve tried an ollie kick-flip – you’ll know skateboarding’s also a mental challenge, a whole new skill set to be learned. What else would the fiftysomething brain and body need?

Not to mention the fact that, when I’m trying something like a kick flip – when, in other words, I’m trying something ‘under pressure, and with effort and attention’ – it’s one of the rare times in my life that, for practical reasons, I’m literally not thinking about anything else. In other words, this is a rare instance of my achieving a state of mindfulness, which, according to Aleman, not only has all the well-known meditative benefits, but also stimulates activity in my brain’s pre-frontal cortex. Slamming!

That balding man skating in the parking lot: he’s not having a midlife crisis.

He’s just showing that he’s still alive.

Leave a comment