Most serious injuries occur within the first month of use…

I’ve long since recycled the instructions that came with my first and, as it turned out, entirely inappropriate skateboard (and as any skater might tell you, the fact that it actually came with instructions was a bit of a red flag). In my case, anyway, the warning was way off.

It actually took eighteen months.

Though perhaps the signs were there from the start.

About an hour into my very first visit to an indoor park, Easter 2023, one of the trucks on my brand new board cracked like a chocolate egg – a whole shiny sliver snapping clean off. I carried the board and the broken piece forlornly to the counter, where the owner told me, in plain terms, I needed to buy a proper skateboard. The rest of the afternoon I rode on a rented deck, apparently (judging by the bruises I returned home with) trying to do to my fifty-one year-old frame what I’d just done to my shattered trucks.

At the end of this September, now fifty-two, I did just that.

In the end, as irony would have it, my undoing was the simple rock-to-fakie. The same move, as I discussed a few months back, that I’d made such a mountain out of failing: the one on which – as my daughter, fatefully it turned out, told me that one time – I was going to have to fall before I got it done.

The rock-to-fakie is an innocuous way to go; a bit embarrassing, maybe, given its relative ease. But then I’m not completely daft. I’d never be doing a trick I knew was going to put me in obvious danger. In truth, it never occurred to me that the trick could be dangerous. Until, that is, and in a way I still can’t really articulate, it was.

If I knew how it happened, it wouldn’t have, because I would have been in control (or as much in control as is possible when you’re falling). All I remember is the sense of coming back down the ramp without my board beneath me – then the awful flop of my foot literally folding underneath my own body weight. Followed by a pain I’d rarely felt ever before.

My immediate thought was not the possibility that my ankle, as a nurse subsequently told me, had broken like a piece of crockery. It was how long I’d have to wait until I could get skating again. Not, as in, weeks or months. But how many minutes. As if it was simply a case of patching it up and getting back to my session.

Realistically, I now understand, it could be several months, half a year, maybe a whole one, before I think seriously about skating again. But I also know, now, that returning to my board is more than just a matter of time.

Breaking a bone doing something you love – especially when it’s a bone so crucial to mobility – is doubly punishing. Not just because it lays you up, unable to easily walk or travel (though that’s annoying enough). More, because it puts that same object of devotion under scrutiny. Right now, in the reality my accident created, skating is clouded with caution and doubt. But in the alternate reality, one in which the accident never happened, I’m not just still skating. I’m skating with impunity.

Back in this strand of the multiverse, by contrast, there’s a part of me that wonders how I will ever get back on the board. But there’s also a part of me that wonders if I even should.

In the alternate world, the one that split from my timeline the moment my ankle cracked, my choice to skate impacts only on the odd hours I devote to it. But back here, now, the implications no longer involve just me alone. I’m writing this just a few miles or so from where the accident happened, which is also the place where I work. Convenient, in a sense – or it would be, if only for the fact that my family lives three forbidden hours’ drive away. And since I’m not a professional – and because skating therefore offers no financial incentives – returning to skating, and risking further injury, might mean neglecting my job as a partner and father.

In some respects, I don’t really need such disincentives. The brutal truth of a serious sports injury is that its harm turns out to be less physical than psychological. Things which up to now I had done more or less automatically, with little thought to its potential danger, I now know will be fraught with uncertainty. This potential for injury is, of course, part of the everyday reality with which any professional athlete simply deals. But in my case, confronting the fact is not just a matter of statistical probability: it’s become a question of morality.

I did plenty of falling my first day at that skatepark, both with and without my sketchy board. Not long ago, the same owner – the one who told me to get a better board – admitted he’d been watching me carefully that day; intrigued, firstly, by my age, and also, perhaps, deeply concerned. But struck too by the fact that, even after falling numerous time, I got back up again.

But then of course I would. If I didn’t realise it then, I now know that this was when I became a skater. Getting up again is what skaters do, since for the majority of the time they are failing, which also means they are falling. Their commitment is not measured in the amount of time they stay on the board (which in itself is not hard), but the number of times they challenge themselves, fall, and get back on.

So much of what I’ve explored in this blog has been based in this simple fact: an understanding of the virtues of confronting fears; of repetition and endurance as a discipline; of the character involved in choosing to get up once more.

But is there ever a time, like this one, perhaps, when the better choice is to stay down?

Maybe not in this case.

Or at least, not quite.

If I’m learning one thing from this enforced break from skateboarding, it’s that I really miss being on the board. At the same time – and here is the surprise – I’m also learning to live without it. Or rather, to work out how much, exactly, I really need it, or don’t.

As easy as it would be to beat myself up about what happened, I try to be as kind to myself as I can: to remind myself, in truth, that I wasn’t doing anything I hadn’t done before. Yet the nagging thought in my head, certainly for the first few days afterwards, was how easily it might have been avoided. The truth is, seconds before it happened, I was telling myself that I’d tried the damned rock-to-fakie enough times. I was probably quite tired, and consequently less focused than I ought to have been. Failure, in this case at least, was making the process feel more like a chore. I was on the verge of stepping away and doing something else – stepping, that is, into that parallel universe of impunity – until I told myself to give it one more go.

At that moment, in every respect of the term, I was pushing it.

Fate, despite what anyone might say, isn’t really there to be tempted. Fate is luck, good or bad, but it’s also an outcome of your decisions. Was the desire to give it one more go,against my better judgement, one way to provoke what happened? Perhaps. But more significantly, I also find myself pondering my own relationship to what I was doing at the time. In pushing it that far, I might ask, what was it serving? Was I doing it for myself? Or was I, rather – in what is actually the textbook definition of addiction – at the mercy of a higher power from which I couldn’t extricate myself? That insistent, perfectionist demand that you attempt the trick, and that you keep trying it until you get it done?

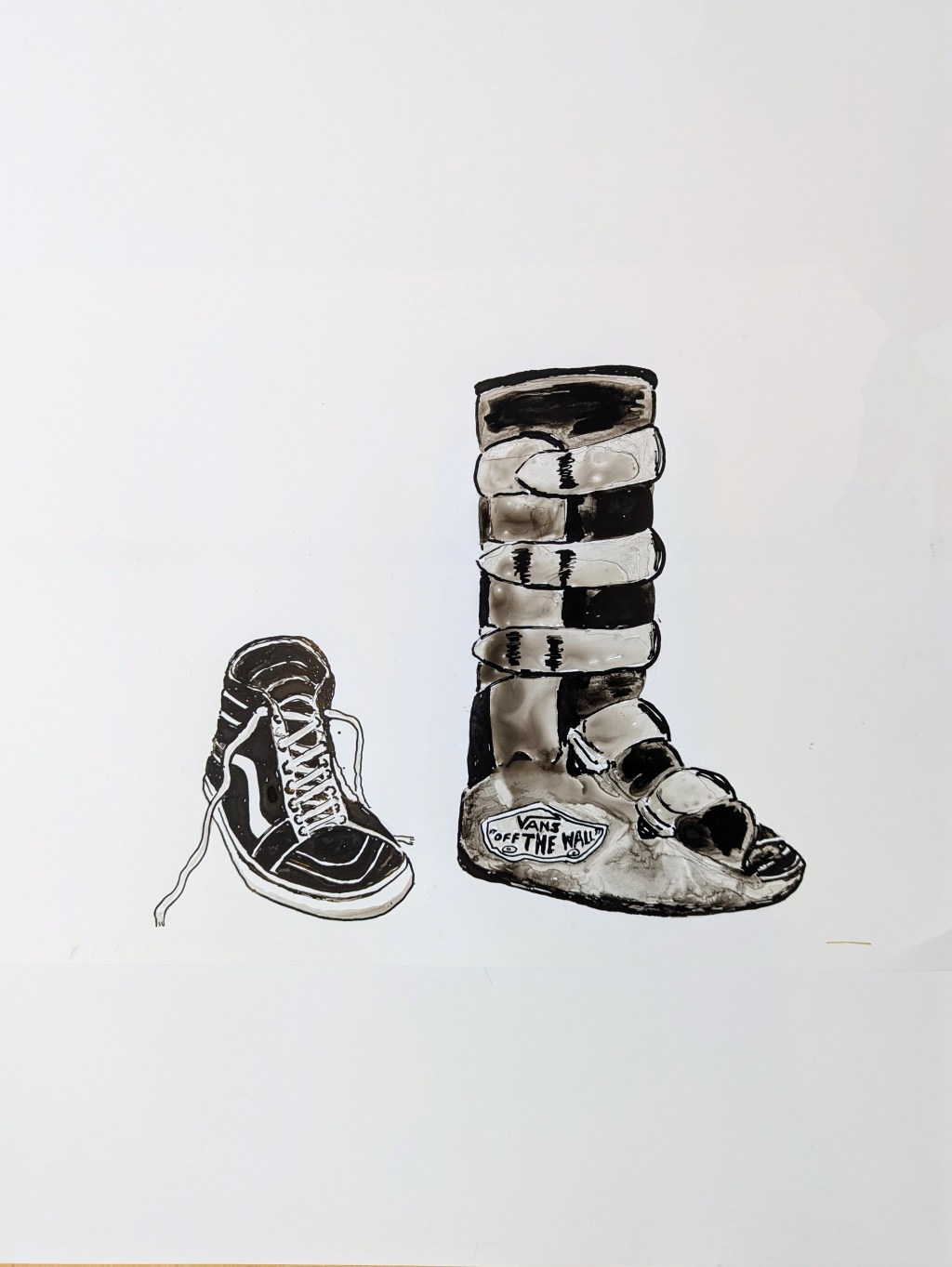

Hindsight clearly shapes this whole complex set of musings (if I wasn’t sitting here right now with my foot in an orthopaedic boot, I’m sure I wouldn’t give such thoughts the time of day). But in the same way that I knew, before crashing out on the ramp, that I had probably had enough, I also remember having had to fight a basic reluctance to leave home that evening and head to the skate park in the first place. My daughter was in London with her mum, which made it a good excuse to head out, even if – as I’ve said before – skating with my daughter is half the joy of it. So why did I go?

I’d actually been skating more than usual those days, most often alone, seemingly getting out whenever I had half a chance. For the first time though in many months, perhaps ever, one of those sessions left me with a profound sense of dissatisfaction, as if I had both not done enough, and not done the little I had done at all well. I was chasing some kind of attainment, but a pedantic one, dependent on ticking off my assigned goals. As much as I grasped them at points, for the large part, these goals remained out of reach. And yet, that evening at the end of last month, when the opportunity again presented itself to me – again, against my better judgement – I went along.

I was, once more, pushing it.

So what, finally, do I come away with from all this?

I started this blog with the positive expectation to take what I could find, philosophically, psychologically, spiritually, from what I feel have always been the positive contributions of skateboarding to my life. But in exploring what it means to learn to skateboard after fifty – which, to pick over the finer detail, is what this blog is really about – I have to take the rough with the smooth. To embrace the possibility for both failure and disaster as parts of this same experience, and not simply to erase one side in order to make a better, but much less honest, story.

I both need and want to accept, in other words, that such setbacks aren’t necessarily an obstacle. That in fact, they might themselves offer ways of thinking, and their own kinds of forward progression. It’s a bit like street skating: you make something out of what you’re given. Equally, I have to make something of the place I’m in now, because what other choice do I have?

In my case, moving forward perhaps means taking a step back. When I skate again, whenever that might be, I know I’ll be in the rare position of getting to pick it up all over again. That makes me lucky, in some ways. And I know, too, how grateful I will feel for the gift.

How restrained I might be by my own scrutiny, my own anxieties, remains to be seen. Perhaps inevitably, and indefinitely, I will prescribe limits that weren’t there before. But then again, I don’t live at the service of skateboarding. I make skateboarding work for me. And if I can keep doing that in terms of joy, and of fun, then all the better. Maybe, within these parameters, I will find things to do I haven’t even envisaged yet.

And even if I can’t make a table, as someone wise once said, then I can at least come away with a chair.

But what to do until that time?

Across this blog, what this whole enquiry has brought to light is that skating, in some ways at least, is the physical manifestation of a whole state of mind, its lessons ones that operate far away from the contexts of concrete and plywood ramps. What kinds of skating mindset, then, might I apply to this break in my skating life?

Can skating help me to keep coping, even when I can’t get on a board?

That, my friends, is a whole other question.

Leave a comment