So, I’m back. Or at least, one version of me is.

If you’ve read some of my previous posts, you’ll know I broke my ankle while skateboarding last September. By the end of the year, still with some reduced mobility, I was physically able to skate again. Mentally, though, was a different proposition.

The physiotherapist I’d been working with this time, to her great credit, never talked about compromise or setting realistic boundaries: it was, for her, always about getting me back to the person I was before the accident. The thing is, I’m not sure I was either ready or even able to be that person again.

Though perhaps I didn’t even want to be.

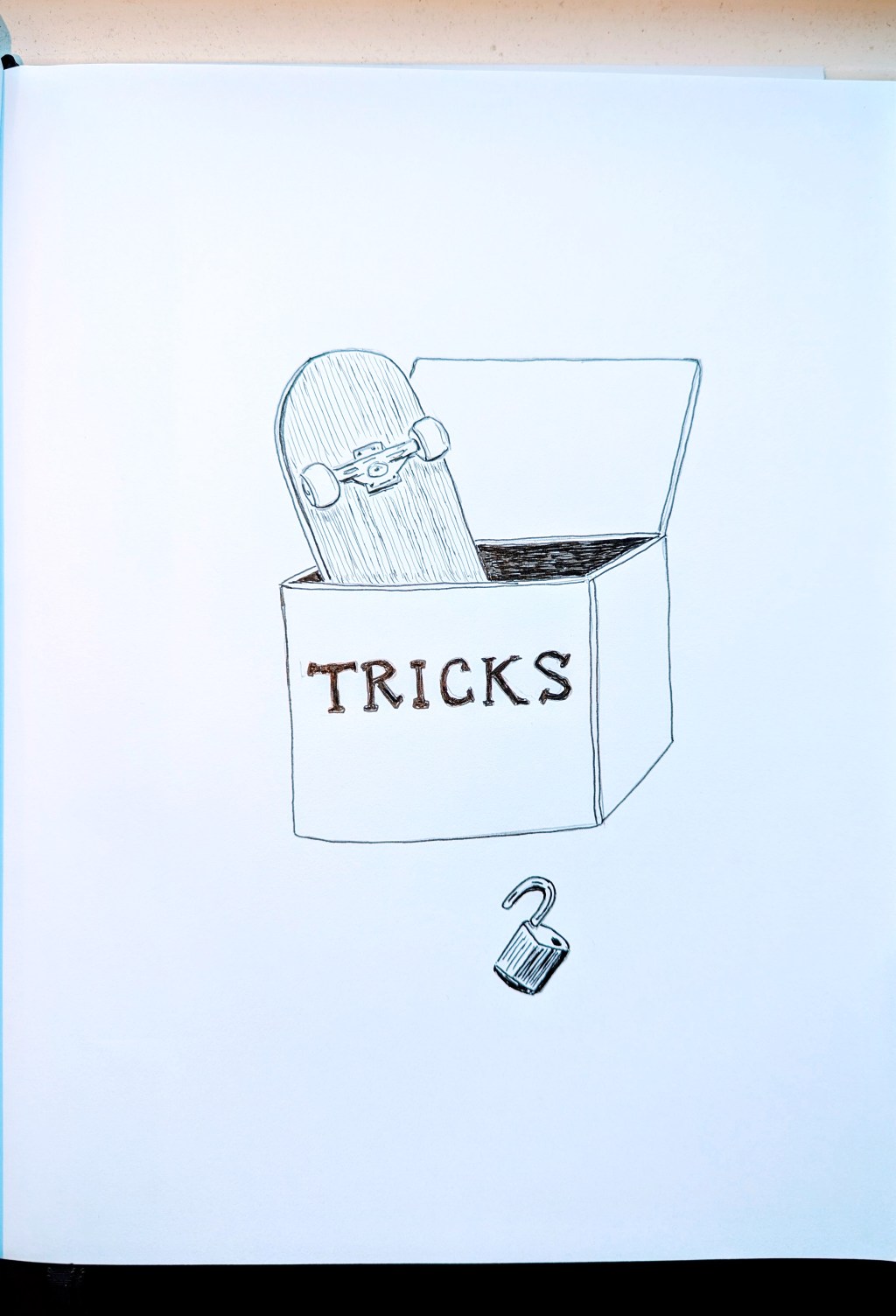

Much of what I’ve thought about in this blog, and even more so during the break between this and my last post, is to do with the targets we set ourselves. Skateboarding is especially prone to this ‘targeted’ way of thinking because we inevitably see progress as a series of increasingly difficult tasks – tricks, in other words – that need to be completed. The thousands of videos showing us ‘how to’ do these things only give us more incentive to try and reach these goals. But thinking about things this way can be damaging when it creates a set of demands you’re not, even with the best will in the world, competent enough to meet. That kind of mental insistence that you have to get it right can cause stress at best, and at worst – as I discovered to my cost – accidents.

One benefit of being physically laid-up, during which time I literally had to find my feet again, was that it gave me time to listen to my body and what it was telling me at this specific moment in time; time, also, to work out the difference between what I thought I ‘had’ to do and what I might actually want or need. The philosopher Oliver Burkeman ponders this same question of our lives’ ‘aims’ in his recent book Meditations for Mortals, where he suggests that our obsessions with goals, on finding our ‘purpose’ or ‘life task’, misses the entirely reasonable point that at a certain age we’ve probably found them already; or at least we would have done, if only we’d stopped looking towards some phantom horizon or imagining ourselves to be people we’re not.

This isn’t the same as compromise: it’s a case of being attuned to the distinctive skills and qualities you’ve spent a lifetime homing, and not dwelling on the ones you haven’t, and maybe, for totally practical reasons, never will. A life task, Burkeman argues, has to be the one you’re living: it ‘emerges, by definition, from whatever your life circumstances are. It’s what’s being asked of you, with your particular skills, resources and personality traits, in the place where you actually find yourself.’

After reading this, I began to think about what, if anything, my skateboarding ‘role’ was. And rather than do what I thought I ought to do, I started to find out the things I wanted to do. One of these things turned out to be a pleasant surprise.

Freestyle skateboarding enjoyed something of a heyday back in the early- to mid-1980s, when a certain Rodney Mullen dominated the sport. By contrast with the huge airs of vert skating, to which it was always a bit of a sideshow (often literally so, when the competitions happened on flat ground near the ramps), freestyling focused on intricate skills and the most imaginative use of the board’s dimensions, often – and in Mullen’s case especially – with the skater barely moving from a fixed spot.

With little appetite just now for bowls and ramps, I turned instead to some freestyle tricks to see how these panned out. I quickly picked up a move in which you kick the tail of the board out from behind and spin it 180 degrees under your front foot, which then catches the nose in reverse. This leaves the whole board stuck out at a raised angle in front of you, onto which you can then hop and ride away; or better still, jump onto while grabbing the new nose with your fingers and spinning the whole board 360 degrees. Or from the same starting point, you can spin complete or multiple rotations; the same principle as a manual but pivoting on just one rear wheel.

All well and good, though the current holy grail remains the casper stall: a two-part move that involves turning the board over with your feet, placed diagonally facing each other, so you end up with one set of toes underneath the upturned nose and the other on top of the tail. After which, you kind of shove-it-scissor-kick the whole shebang so it does a half-rotation on both axes, bringing you back to where you started (ideally). Like anything else, of course, there’s no point me telling you this: you really just need to see it done. It’s cool as flip.

And at least where I’m at, I’m the only one that seems to be trying it.

Despite its brief moment in the sun, freestyle became something of an endangered species with the explosion of street skating back in the 1980s and 90s. This probably owes to many reasons. It’s less obviously visual than vert or street, for one thing, its nerdy technicality a contrast to those other forms’ more brash and spectacular dimensions. Freestyle’s also kind of perverse, to be honest, in that it will often use the board in a way it was never ‘designed’ to be used, a bit like riding a surfboard on the sand. But I suspect that, at some level, there’s a deep sense for some that freestyle is just not man enough – it might be a telling point that in two years, I’ve only seen two freestyle skaters in the flesh, as it were, both of them women, and both skating alone – and that all that noodling around within a few square metres of flat ground couldn’t have any of the thrill of deep ramps and high walls. When Mullen, partly by economic force of circumstances, reinvented himself as a street skater in the 1990s, one early add showed him nose-grinding a kerb along with the words: ‘Just another gay freestyler’. Intended ironically, I know. But still.

(The bigger irony here is that much of what came to be called street skating was basically freestyle in motion and adapted to an urban terrain. The flat-ground ollie, by now the default means via which skaters hop onto a kerb or any other raised surface, was invented by Mullen as part of his freestyle repertoire; as were a bunch of other tricks, such as the kickflip, that derived from that foundational move. But hey, that’s just history, and no one likes a lecture.)

A while back, around the time I was re-reading Mullen’s autobiography, I happened to come across Lou Reed’s song ‘Doin’ the Things that We Want To’. Hearing it for the first time, I figured it was just some paean to slacking off; until, that is, I bothered to listen closely. Reed is talking specifically about art, and more specifically still about artists who (not unlike Mullen) work in the pursuit of a singular kind of vision and style. Sometimes work, especially in Reed’s world, is much more fun than doing nothing.

For that matter, doing what you want to is much tougher than it sounds, because it means working out what you really want to do, and not what you think you should do: nor what, for that matter, anyone else thinks. Not coincidentally, at the same time as hearing this song I found out that Reed had been a serious practitioner of Tai Chi; so much so that, towards the end of his life, when his health was poor, it was pretty much the only thing he wanted to do. Which in its own way – like any artist who decides, because it isn’t right for them, not to make art anymore – is also an act of courage.

I’m not going to pretend that there’s anything specifically courageous about my newfound embrace of freestyle, but it does take a certain kind of self-understanding to do whatever it is everyone else is not doing, and not as some pose, but because it feels right. I can’t pretend to be any good at it (yet). I’m no artist, either: to mangle T.S. Eliot (as if I needed an invitation), I am no Rodney Mullen, nor was meant to be. But that’s the beauty of it. Playing around with freestyle was a response to where I ‘found myself’ at this particular moment, since it started as an accommodation to my still healing ankle. At first I merely saw it as part of the process of rehabilitation, until I worked out that the process might just be the real thing – an end in itself.

In short, I was finding a way into something via another door, making the thing work both for and with my abilities, and not stretching to reach goals more realistically designed for another person. That’s because I can’t ever be that person; just as, equally, that other person can’t ever be me. Whatever you do, so long as it’s what you really want, is always a unique expression of the unique person you are in that space and time. Lose sight of that, and all you can be is someone you’re not.

Leave a comment