Before getting injured, I’d always mistaken a setback for a pause button, and recovery the time you spent waiting to get back to normal. In the same way, I’d always thought therapy was something you did only when something needed fixing.

Both of these assumptions, I’ve discovered, are completely wrong.

I’d already been told that full recovery might take as much as a year. I didn’t believe that, but as it has turned out, this was more or less on the button: exactly twelve months to the day, in fact, there was still some lack of extension in my left lower leg. My first session of physio back in October 2024, though, revealed that this extension was practically non-existent. So I left that same afternoon with a list of basic stretches and flexes which I might, in other circumstances, have laughed at for their simplicity, but which I slowly came to understand were not just challenging but necessary – at least if I wanted to do anything soon that was remotely vertical.

But I also came to grasp that these exercises were not merely steps towards some fabled recovery on the horizon: that point when I could finally press ‘play’ again, and I’d be back to where I was before. The work of therapy in itself, I saw, might be part of the adventure.

There’s an important humility to undergoing physiotherapy, not dissimilar to the kind of humility I suggest we practice when doing skateboarding itself. It involves, for one thing, a recognition of physical limits. But it’s also illuminating. Physio, as I touched on in my last post, turned out to be a different but no less valuable process of finding my feet. It was a way of discovering their limits and how much I need them to work, like being introduced anew to my body, rather than merely reacquainted, which suggests no more than a return to the place where you began. In this case, it was more like going to a whole new point of origin.

Much like most of us know nothing about our cars until they stop going, we know so little about our bodies until they break down. Physio, as with any kind of bodily recovery, is from this perspective a bit like looking under your own bonnet. And besides being the opportunity to build new strength in my limbs that hadn’t actually been there before, it was also a chance, to quote a phrase, to make a few modifications.

I’d never have known any of this if, of course, I’d simply treated physio as something to plough through in order to get back to what I’d been doing before. In place of the blunt-instrument attitude to recovery that sees only one goal, listening and feeling your way through therapy allows you to see instead a dozen other possibilities. Call this a kind of mental flexibility – I think the term in vogue is ACT, for Acceptance and Commitment Therapy – which can see unplanned and otherwise undesirable outcomes as opportunities for doing something else. Seeing this in active terms is also a lot less woolly than mere ‘positive thinking’, which always strikes me as too vaguely acquiescent and hopeful. It’s the ability, in other words, to shift your mental weight when need be, and to give attention to the unforeseen and unknown.

By New Year’s Eve I’d progressed to my first physio session in the hospital gym; a place I’d somehow imagined as a sort of soft-play with more sweat, but which turned out to be more like an actual gym, only with less testosterone and better music. Even if it hadn’t been there for her to see on her case notes (presumably around cause of injury), my therapist marked me down as a skateboarder from my first visit, noting the somewhat beaten-up Vans I had to take off so she could get to my equally beaten-up ankle. Perhaps this is why, as she now took me around the gym, she gave especial attention to one particular piece of equipment.

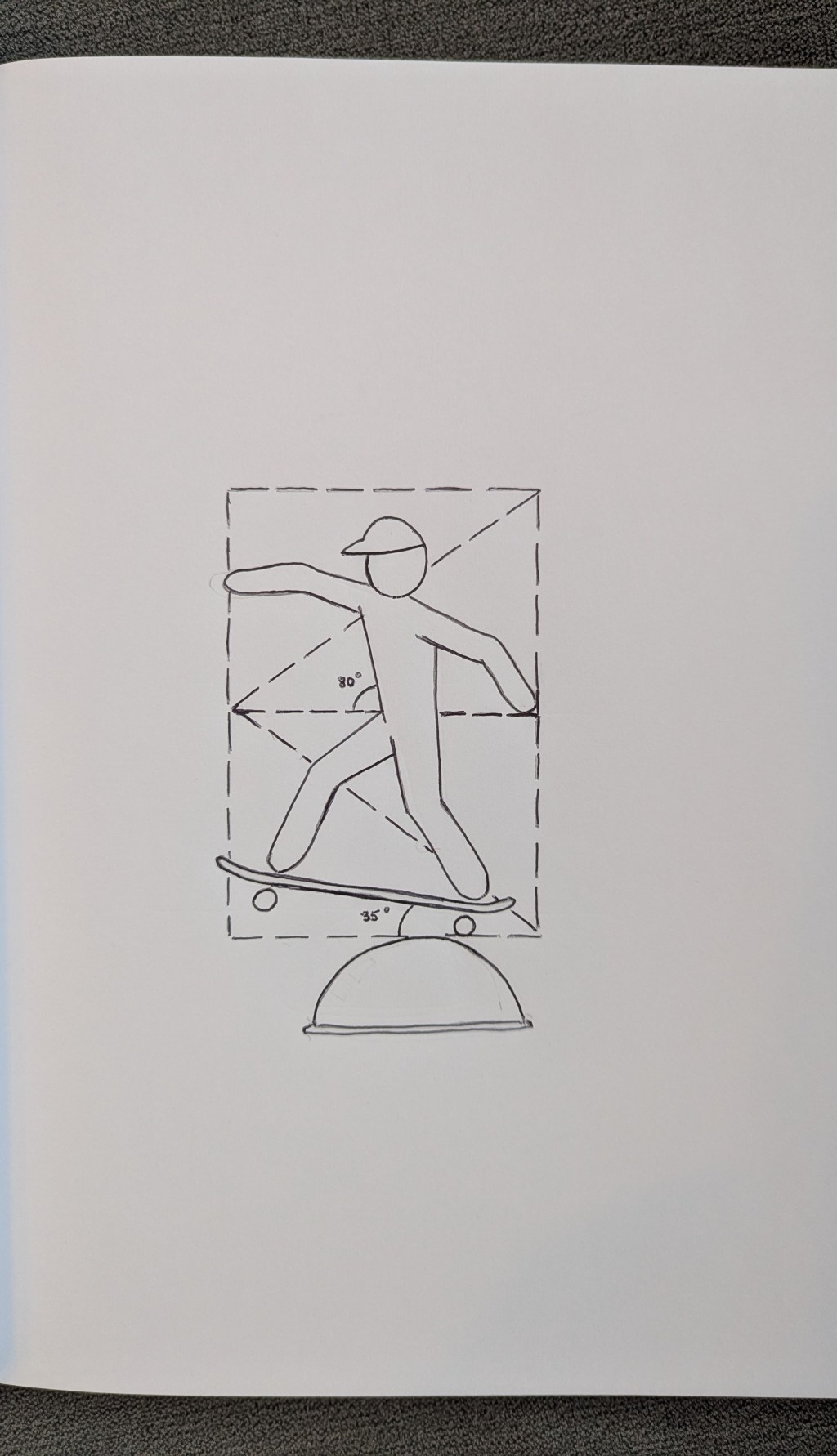

If you’ve ever worked with one, you’ll know a Bosu ball is not a ball at all but an inflated, two-foot-diameter half-sphere balanced on a plastic base. You can do all sorts of actions on the squishy dome, or, flipping it over, stand on the upturned base, allowing it to tilt at any angle or rotate. Standing with my feet at either side of this disc, my aim that day was to shift my weight as far as possible across or around without allowing the edge to hit the ground. In other words, while constantly moving, I had to keep the disc in a perpetual state of balance.

Working this tiny circle in incremental adjustments, fighting against the ball’s gravitational desire to simply topple over, reminded me just how much skateboarding operates in the same delicate zone; a seemingly unsustainable but finely poised place of tension, with the rider working to make the board not do that to which it is gravitationally more inclined.

As it happened, these exercises also chimed precisely with what I had started to explore on my tentative return to skateboarding around this same time. As already noted, I was now back to wearing two shoes again instead of just one, and was starting to think about what I’d actually do once I got back on a board. I knew that, even if I’d wanted to go back there at some point, bowls and bigger drop-ins were for the time being out the question. But I wasn’t sure either that my ankle was ready to face the battering even novice tricks on the flat would imply. So I decided, for the time being, to keep the weight off my left foot as much as I could.

The solution, naturally, resided in the manual.

Not the rulebook, in this instance, but the skating trick that involves riding solely on the rear wheels, the most basic aim being to go as far and as long as possible in that held position. Until this point, I admit, I’d never given manuals that much credit. In my mind they were too redolent of wheelies, which sometimes seems like the only trick bikers are capable of doing. Perhaps that’s unfair on bikers. I know now it’s definitely unfair on the manual.

There’s a reason even top pros play around with manuals, which is that, while lacking physical risk, they’re a test of precision and sustained control. Too much downforce on the tail and you’ll fall back; too much towards the nose and you’ll drop forward again onto four wheels. At the same time you’re also trying to steer, which is harder on two wheels, where every adjustment is more magnified. And maintaining all this is the precise geometry of your upper body in relation to the board, striving to protect that Goldilocks Zone of balance for as long as it takes.

I soon discovered that, in this process, doing manuals is deeply satisfying, even addictive, unique also for the way its satisfactions don’t rely on the completion of split-second, intricate combinations of moves. The manual, in its essence, is not that hard: the difference, and the degree of pleasure it affords, depends on how long and how cleanly you can keep it going.

To hold a manual for as long as possible, even if (in my case) this might be just half a dozen seconds, is also serenely meditative. Neither passive nor explosive, it is poised somewhere in between, in such a way that a manual feels oddly weightless – which, since it involves keeping your centre of gravity sustained over the board, is probably close to the truth. It’s for this reason that the manual is most successful when it feels like you’re not doing anything at all, because the moment you feel like you are, you’re done.

Like the Bosu ball, it’s also great therapy: trying not to fall over not only activates a myriad of muscles and inner receptors, but is also, quite obviously, a wonderfully effective way of lasering attention towards an immediate task that forbids distraction. This is not to say that doing manuals will cure all ills, make you live longer, or bring about world peace. What I do know is that holding for as long as possible those oppositional forces within the same time and point in space brings on a serene centring of attention: a kind of calmness in the middle of all the cacophony.

In a more metaphorical sense, too, this same focus on hesitation and the distribution of weight also spoke to my new and now ongoing relationship with skateboarding: understanding, in other words, the calibrations of my own desires and instincts. That recognition of when to go, and of when not to; the consciousness of balancing ambition with realism, or of immediate compulsion with long-term goals; to determine by my own actions and amusement what were the ‘rules’ of the game, rather than follow ones that didn’t really exist. That effort, above all, to slow down, and to carefully negotiate all options and their consequences.

If only all our decisions in life could be made with such poise.

Leave a comment